Indistinguishable from magic

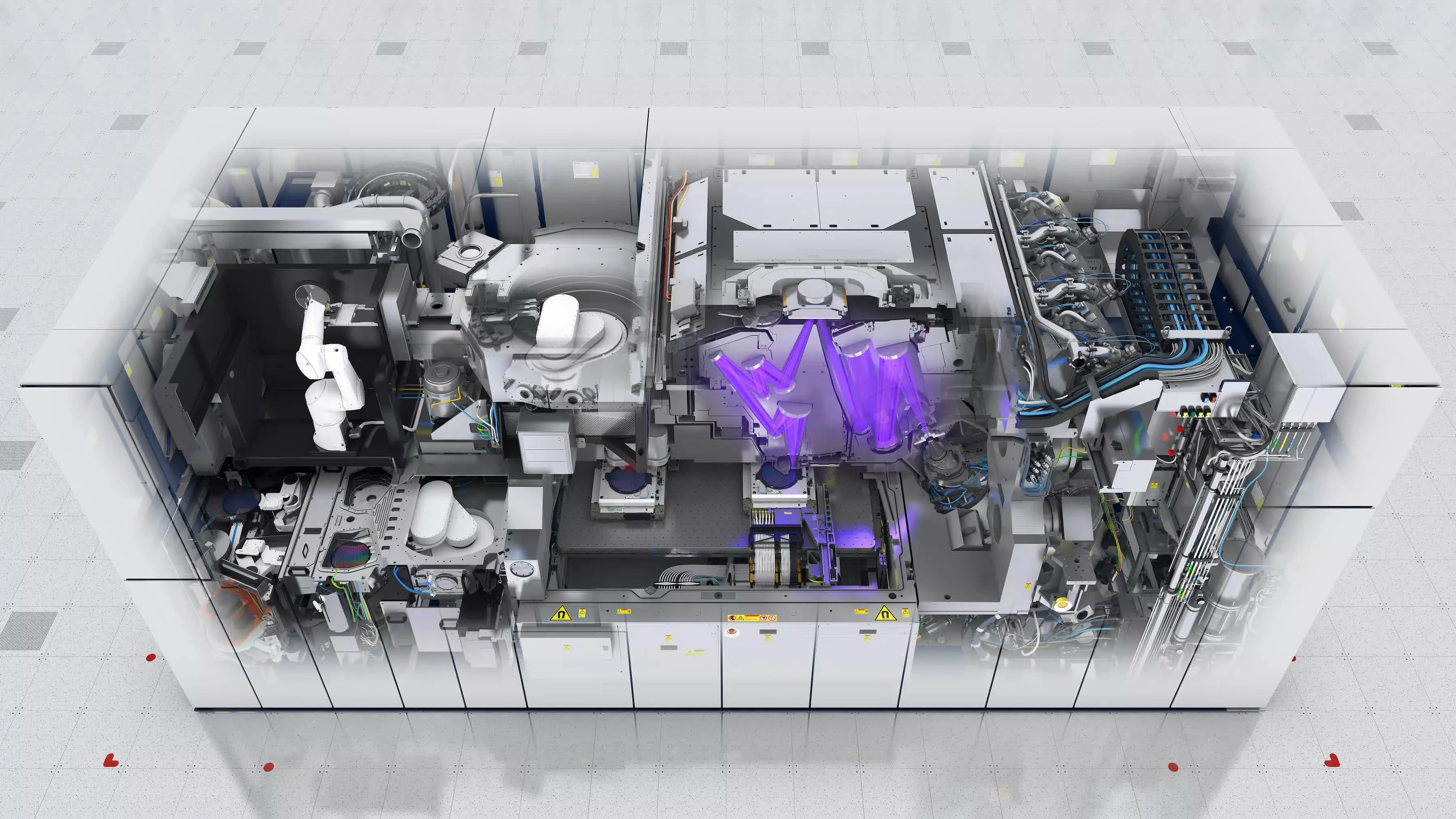

Credit: Illustration of an apocalyptic ASML lithography machine, own work, using gpt-image-1

Just under a year ago, I was talking with some friends about how much people like “retro” technology nowadays. I argued that today anyone has the best cameras of the moment in their pocket and yet they still prefer to buy single-use cameras, like the Kodak FunSaver.

The conversation drifted and I commented that the same thing happened with music. Today, you can open Spotify, play any song ever created by human beings instantly and enjoy it in the palm of your hand. Even so, the vinyl section in shops seems to do nothing but grow. “Maybe vinyl is the disposable camera of music,” I insisted.

Then one of my friends said that vinyl had its own “charm”. She found it incredible that music could come out of that thing; on the mobile you just hit play and that’s it, but vinyl records were… magical.

That reflection from my friend prompted laughter from those present, but it got me thinking. I spoke about it with other people and many told me they shared my friend’s point of view: the mobile just works, it’s intuitive, but music coming out of a vinyl seems like a magic trick. Does the iPhone have such good design that no one is surprised by how it works, or are we simply no longer amazed by magic? I wondered.

Some time ago, I had read a phrase on this subject, and it came back to me during those conversations. The phrase is from 1973, when Arthur C. Clarke formulated his three laws. The third law said the following:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic 1

So I’ve decided to write this brief article to try to make my reader believe in magic again. We’ll go step by step; I’ll show you three tricks. I hope to surprise you with the magic that surrounds you in your daily life. Don’t look for the trick, behind the curtain there will be no emerald wizards, just people—brilliant people.

First trick. The stone that sang.

Let’s begin with a somewhat old trick. The first to perform it successfully was the magician Edison in 1877 2, and later it was perfected by the magicians at Columbia Records in 1948 3—yes, the same label that gave us Marc Anthony, Mariah Carey, and Julio Iglesias.

For this trick we need several materials. A bit of molten vinyl, a wax mould, a needle, and a plastic cup to which we’re going to recite a lovely serenade.

First we’ll attach the needle to the end of the plastic cup; then, when the plastic cup vibrates, moved by the emotion of hearing our serenade, it will also make our needle vibrate.

We’ll place our wax mould on a platter that we’ll spin (very carefully to keep a constant speed, such as 33 full revolutions per minute).

After that we’ll place our cup-with-needle—which I’ve decided to call a microphone to keep the magical nomenclature—over the rotating mould. Now I sing a lovely serenade, for example: Me olvidé de vivir by Julio Iglesias.

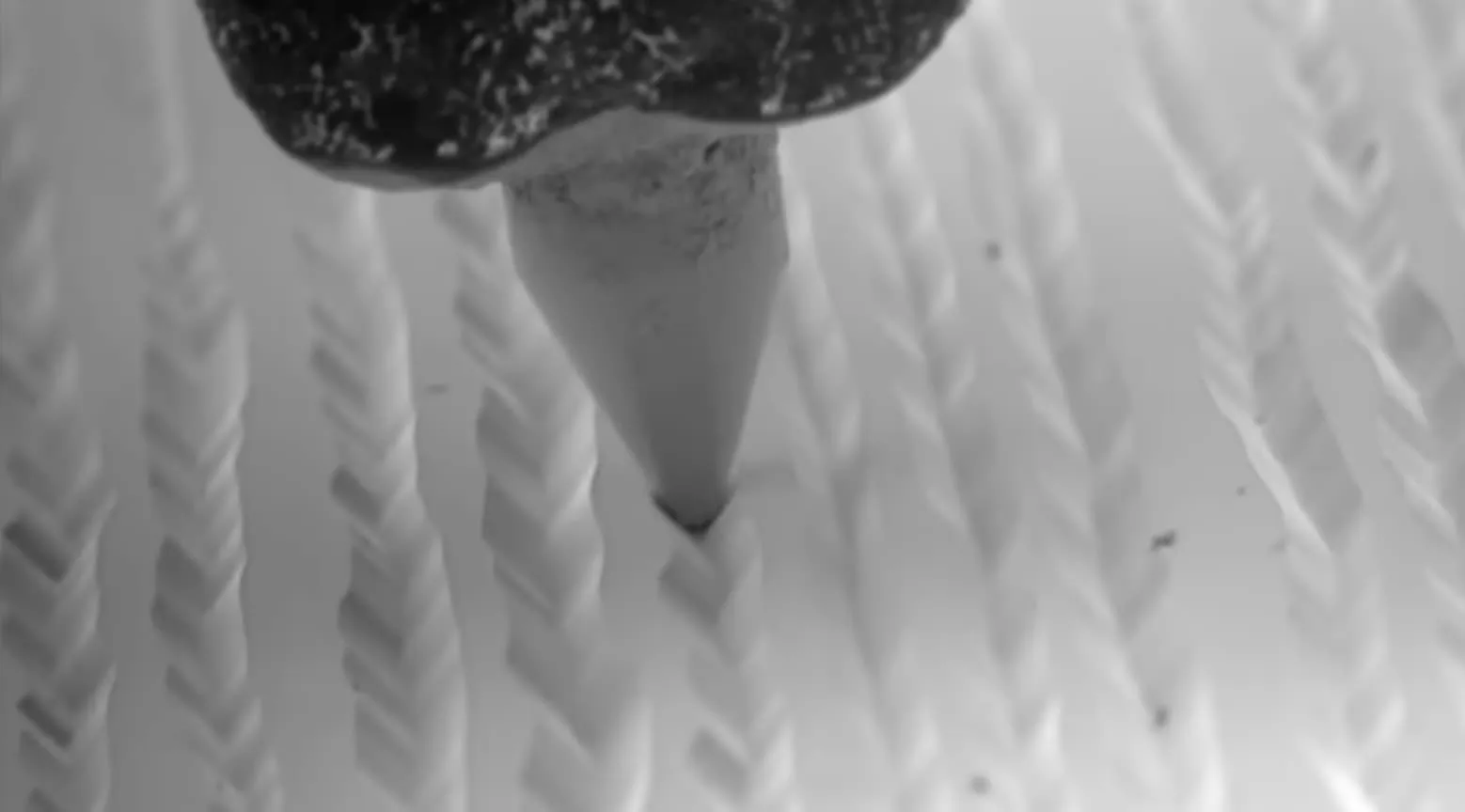

After my microphone has endured my entire performance, we’ll be left with a wax mould scratched to bits. If we look very closely at the mould, we’ll see that the grooves left by our needle are not symmetrical. This is because we’ve written into the mould how our song sounded.45 Here’s a photo of my needle recording “Me olvidé de vivir ft. Pablo Portas” (not really my photo, but to help you picture it).

If we now take the wax mould and press it onto our pile of molten vinyl (after hardening the wax or transferring it to a metal mould), we will have created a copy of our song and we can sell it to whoever is unlucky enough to listen to us sing. When they buy our record, without realising it, they’ll perform the final part of the magic trick.

Using their plastic cup with a needle—or more likely a turntable, let’s be honest (though both would work6)—they’ll reverse our recording process: the playback.

The needle will pass over the vinyl, bumping into the grooves of the disc; that will make our plastic cup vibrate, or, failing that, a copper coil in a modern turntable.

If we bring our ear very close, we’ll hear ourselves singing again, very softly.

The volume problem is solved either by building a larger loudspeaker, like the ones in old phonographs (that’s why they were so big5), or by amplifying the sound electrically; that’s why modern turntables use a copper coil in front of a magnet. If we then “amplify” that current, we can make a “cooler” diaphragm vibrate, like the speaker in your turntable.

Herein lies the magic of the record player. If you want to see the “plastic-cup microphone loudspeaker” in action, Jaime Altozano has a video performing this magic trick.

Second trick. The stone that counted.

For my next trick, I’ll use a magic stone: quartz crystal. This magic stone doesn’t come from the Nether, as some gamers might think; it’s the same quartz mined in China, Brazil, or Norway.7

For this trick I must introduce a brilliant magician, Pierre Curie—yes, Marie Curie’s husband, perhaps the first man in science popularly known through his wife rather than the other way round. It turns out that in 1880, Pierre and his brother discovered that if they applied an electric current to quartz, it vibrated at a constant rate.8 Years later, in 1919, another brilliant magician, William Eccles (the inventor of the flip-flop circuit), solved the damping problems of the crystal and managed to keep a tuning fork in constant motion.9

Finally, in the 1920s, the magicians at the UK’s National Physical Laboratory and at Bell Labs managed to create oscillators with this stone that allowed them to keep time precisely. These “clocks” were enormous and kept in ovens to maintain a constant temperature, since if the quartz expanded or contracted, the frequency at which it vibrates would change. Thus their clock would deviate by only one second every four months.10

Until the arrival of the atomic clock in the 1960s, the quartz clock became the standard for timekeeping. In that same decade, cheap semiconductors reached the market, and inventing a clock for everyday people became possible.

“Why were semiconductors needed to make a clock?” you may ask. Because quartz doesn’t vibrate once per second—it vibrates thousands of times per second—so you need to keep count with some kind of electronic device.11

At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Seiko, one of the sponsoring companies, offered its new quartz clock as a backup timer for the marathon.12 Five years later, Seiko launched the Astron 35SQ, the first quartz wristwatch. It drifted by only 5 seconds per month. For 450,000 yen—the price of a car at that time—you could get a gold watch that promised: “Someday all watches will be like this,” and so it came to pass.13

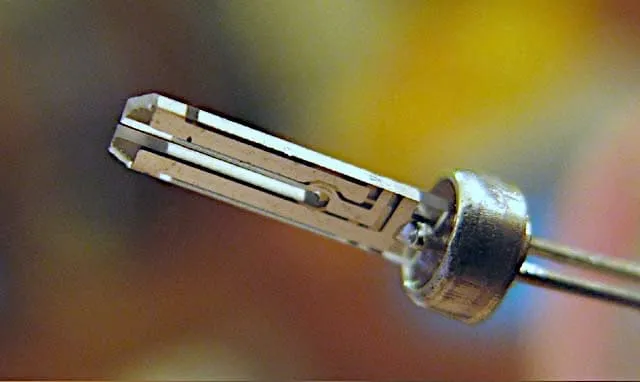

We arrive at the present. The device you see in the image is a modern quartz resonator. Tiny metal wires have been printed to apply an electric current to the crystal’s tines, which vibrate in time. This crystal has been laser-cut into that shape to vibrate 32,768 times per second.11 That number is no accident, as it equals (2^15), a power of two. It was chosen because binary counters find powers of two easier to count.

This little object (or something similar) sits inside every clock around you in your daily life and is what enables the magic trick.11

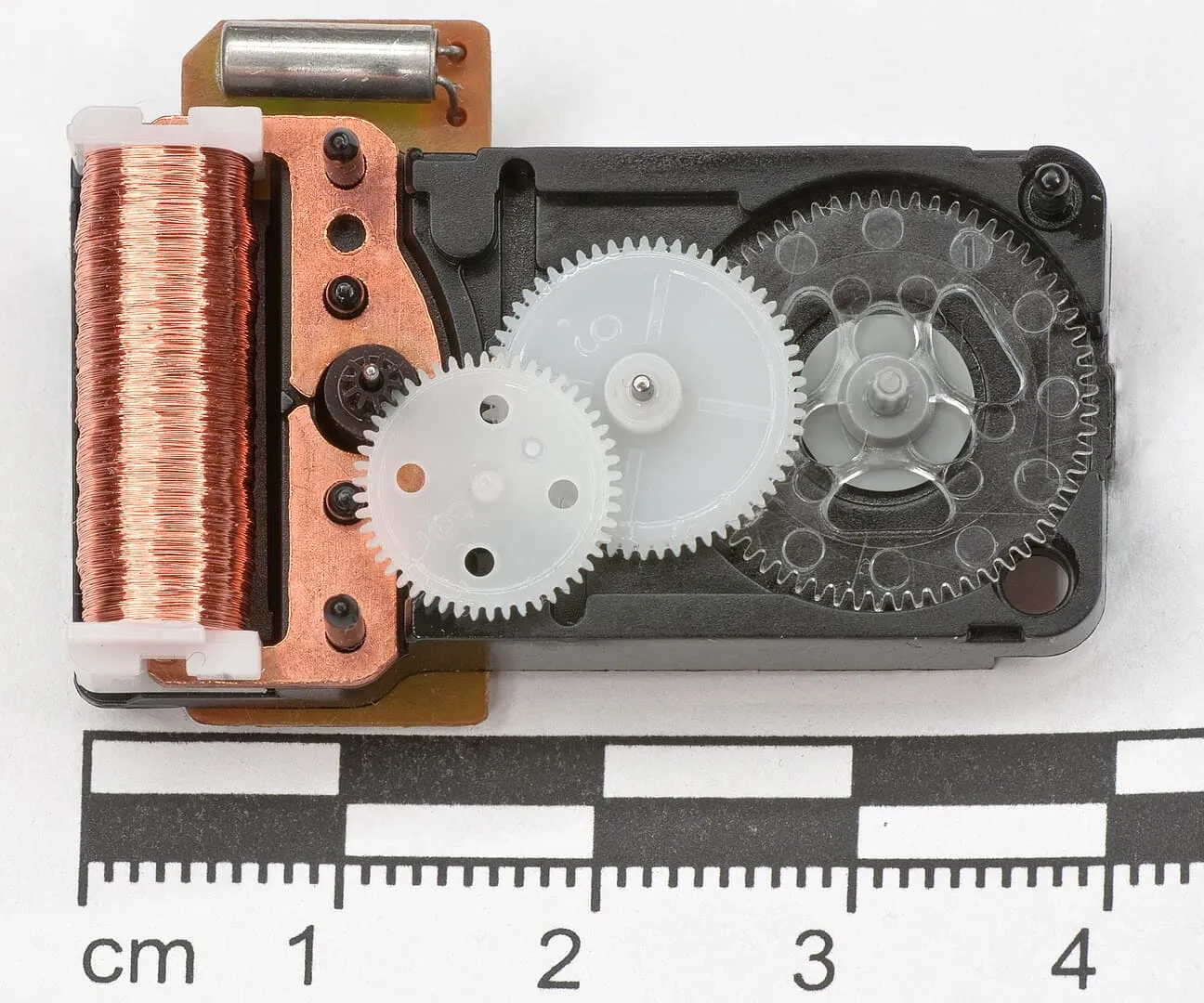

First, we connect the quartz resonator to a battery—it could be a button cell, an AA, a car battery, whichever you prefer. Then, we count each vibration with a binary counter (I’d explain how it’s made, but the article would get rather long), or you can try counting them by hand if your brain goes that fast. Lastly, when the counter reaches 32,768 repetitions, it will actuate a magnet.

This magnet will turn a small gear, which in turn will move your IKEA clock’s seconds hand forward by one second. This, in turn, will advance the hour and minute gears by their corresponding amounts. If you’re curious, take your wall clock down and look at the mechanism above the battery; it should be similar to this. In it you’ll see the quartz resonator hidden under a plastic guard, the electronic mechanism on a small PCB, the electromagnet (the copper coil), and the various gears that move the hands.

This magic trick far surpasses the accuracy of mechanical watches. While the best Rolex can deviate between 4 and 6 seconds per day, a good quartz watch deviates only 5 to 10 seconds per year.14 Perhaps Rolexes are the disposable cameras of timekeeping.

If you’re still curious about the magic of timekeeping, Branch Education has a super-interesting video with animations on the subject.

Lastly, if you’re worried that your mobile’s alarm might go off a second early tomorrow, let me tell you that internet-connected devices synchronise their time with the nearest atomic clock in real time, so even if your mobile’s crystal isn’t perfect at keeping time, it constantly corrects its drift.15

Third trick. The stone that thought.

Let’s move on to my last trick, where I’ll turn a stone into gold—well, not into gold; gold is very cheap compared to what I’m going to create. I will turn the stone into 450 machines, each capable of 10 trillion ((10^12)) operations per second. That is, the brains of 450 MacBook Pros with the M3 Max.16 That’s the key, the great revolution of our time: transistors at their finest—microchips.

But let’s get to it: what’s the trick—how do you turn a €50 silicon wafer into a wafer of processors worth more than €80,000? The key is this machine.171819

A machine the size of a London bus. A machine that weighs as much as two Airbus A320s. A machine that only one company in the Netherlands knows how to make. A machine built in a room cleaner than an operating theatre. The most complex machine of our time. A $400 million machine. The TWINSCAN EXE:5200B.18

Yes, the worst name in history, but when you sell a $400 million machine, marketing matters little. (Important note: I’m going to focus on the latest model of this machine—many have existed before it—but the fundamental idea is the same19.)

In my opinion, this is one of the greatest magic tricks in history. Unlike other tricks, I’ll be brief, as I don’t claim deep knowledge of one of the most complex subjects of our era. However, I’ll try to offer a basic grasp of its essence.

The goal of this machine is to transform the design of a processor—the component responsible for mathematical operations in your device—from its initial size of an A4 sheet to its final size of a few millimetres, much like an ordinary photocopier.

To begin, you need a silicon wafer, slightly larger than a vinyl record. This wafer must be perfectly polished and treated, without a single speck of dust. Consider that the smallest feature of a modern processor is smaller than a red blood cell, so dust is a serious problem in this process.

For our “photocopy”, we will use “extreme” ultraviolet light—light that is absorbed even by air. To avoid this, we will seal our machine under vacuum.18

With a laser, we will strike a tiny droplet of tin with extreme precision; the explosion (the size of the tiny tin droplet) will be hotter than the Sun, and from there our violet light will emerge.

We then need to direct and focus it. One might think, not incorrectly, of using glass lenses. If you use a glass lens, you can burn a sheet of paper—or your eye, if you’re not careful. But ultraviolet light is so delicate that it would be absorbed by the glass of the lens itself. That’s why lenses aren’t used, but mirrors instead. Mirrors so perfect that only Zeiss, the German optics company, knows how to produce them. These mirrors are used to redirect the light and concentrate it.

Finally, the light passes through the tiny apertures of the pattern to be duplicated, bounces off a couple of additional mirrors, and burns the surface of the silicon wafer, etching the desired pattern. This process is repeated for each chip on the wafer (approximately 450) before moving on to the next wafer. A robotic arm inside the vacuum chamber meticulously places and moves each wafer. This process is carried out 185 times per hour.20

ASML, the only company in the world capable of doing this18, has a lovely promotional animation of its machine in operation.

If you’re curious about this incredible machine, it’s not the first of its kind, but it is the most advanced. CNBC has an exclusive report from inside ASML’s headquarters in Veldhoven, the Netherlands.

Thanks to these machines, our mobiles, our watches, our computers, our hard drives, our hearing aids, our MRI machines, our satellites, our artificial intelligences, and soon even our toasters are capable of “thinking”.

For that reason, I consider this the greatest magic trick in humanity’s history (along with the LHC, the ISS, and ITER, of course).

Thanks for reading

This is my first article on the blog, and I hope you liked it! If so, please share it. You can also search Google for “blog.pablopl.dev” and click the link if this blog appears. That would help me a lot to improve my search ranking.

I don’t think I’ll write many opinion pieces like this. Most of my articles will probably focus on computing. For example, my next article will be about how I use Linux inside macOS, and I’ll publish it soon. However, if a topic arises that I’m passionate about or that inspires me creatively, I’ll publish an article sharing my modest opinion.

You can find my sources below. I haven’t made up anything I’ve discussed. If you have a GitHub account, feel free to leave a comment—or simply an emoji—below.

Thanks for reading, and see you soon!

Footnotes

-

A. C. Clarke, Profiles of the Future; An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible, by Arthur C. Clarke. 1973. ↩

-

Wikipedia contributors, “Phonograph,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Nov. 17, 2025. Link (accessed Nov. 17, 2025). ↩

-

R. Shuker, Rock Total: Todo lo que hay que saber. Ediciones Robinbook, 2009. ↩

-

Real Engineering, “The Truth About Vinyl - Vinyl vs. Digital,” YouTube. Nov. 30, 2018. [Online]. Available: Link ↩

-

This., “How does this stuff make sound???” YouTube. Dec. 31, 2023. [Online]. Available: Link ↩ ↩2

-

Jaime Altozano, “¿Se puede crear un altavoz con un VASO? (ft. QuantumFracture),” YouTube. Jun. 12, 2019. [Online]. Available: Link ↩

-

“Cuarzo (HS: 2506) Comercio de productos, exportadores e importadores | Observatorio de Complejidad Económica,” Observatorio De Complejidad Económica. Link (accessed Nov. 17, 2025). ↩

-

C.-E. M. Gómez, “Laboratorio Curie: el generador piezoeléctrico. Museo Virtual de la Ciencia del CSIC.” Link ↩

-

M. A. Lombardi, T. P. Heavner, and S. R. Jefferts, “NIST Primary frequency Standards and the realization of the SI second,” NCSLI Measure, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 74–89, Dec. 2007, doi: 10.1080/19315775.2007.11721402. ↩

-

Branch Education, “How do Digital and Analog Clocks Work?,” YouTube. Jan. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: Link ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

E. E. Mariscotti, Corporate risks and leadership: What every executive should know about risks, ethics, compliance, and human resources. CRC Press, 2020. ↩

-

“The story of 1969 Quartz Astron and GPS Solar Astron | Seiko Astron,” The Story of 1969 Quartz Astron and GPS Solar Astron | Seiko Astron. Link (accessed Nov. 17, 2025). ↩

-

L. Sinozich, “Quartz Watches: Affordable accuracy in luxury timekeeping,” Fink’s Jewelers, 16 May 2024. Link (accessed Nov. 17, 2025). ↩

-

I. Ivanov and I. Ivanov, “Network Time Protocol (NTP),” NetworkAcademy.IO. Link ↩

-

A. Orr, “TSMC struggling with early yields of iPhone A17 and M3 Mac processors,” Apple Insider, Apr. 23, 2023. Link (accessed Nov. 17, 2025). ↩

-

Branch Education, “How are Microchips Made? CPU Manufacturing Process Steps,” YouTube. May 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: Link ↩

-

CNBC, “How ASML makes chips faster with its new $400 million high NA machine,” YouTube. 22 May 2025. [Online]. Available: Link ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Branch Education, “The $200M Machine that Prints Microchips: The EUV Photolithography System,” YouTube. 30 Aug 2025. [Online]. Available: Link ↩ ↩2

-

ASML, “Unveiling High NA EUV | ASML,” YouTube. 05 Jun 2024. [Online]. Available: Link ↩

Last modified: 23 Nov 25